By Annabelle King September 19, 2025

An ACH transfer (Automated Clearing House transfer) is an electronic movement of money between bank accounts in the United States.

It’s the foundation of many routine payments – for example, payroll direct deposits, monthly bill payments, tax refunds, and consumer-to-business transfers – and is governed by rules set by the National Automated Clearing House Association (NACHA).

In practice, an ACH transfer moves funds through the ACH network, a secure batch-processing system operated by the Federal Reserve and The Clearing House (the Electronic Payments Network) under NACHA’s oversight.

The vast majority of U.S. electronic payments use ACH: for instance, NACHA reports that as of 2024 the network handled 33.6 billion transactions totaling $86.2 trillion. ACH is considered safe and efficient – far less costly than paper checks, which NACHA itself calls “the payment type most prone to fraud”.

ACH transfers are used by individuals, businesses, and governments alike. In fact, NACHA notes that 92% of American workers receive their pay via ACH direct deposit, 90.6% of U.S. tax refunds go through ACH, and 99% of Social Security benefits are delivered via ACH.

Essentially, if you receive a paycheck or pay a recurring bill (mortgage, utilities, insurance, etc.), you are very likely using ACH. This background shows that understanding “ACH transfers” – how they work, their advantages and limitations, and how they compare to other payment methods – is important for consumers, businesses, and finance professionals.

The Automated Clearing House (ACH) Network

The ACH network is a nationwide electronic system for financial transactions. It was established in the 1970s (developed by the Federal Reserve and early ACH cooperatives) to speed up and automate payments that previously relied on paper checks or cash.

Today, the network interconnects virtually all U.S. banks and credit unions, making it possible for funds to travel reliably from any bank to any other bank in the country. Two central operators – the Federal Reserve’s FedACH service and the private Electronic Payments Network (EPN) – process all ACH entries multiple times each business day.

NACHA is the rule-making body: it maintains the ACH Operating Rules (a type of payment system standard) that all banks and payment processors must follow.

The ACH network handles credits and debits. An ACH credit is a “push” transaction initiated by a payer (for example, a company pushing payroll into employees’ accounts or a customer paying a bill).

An ACH debit is a “pull” transaction initiated by a payee (for example, an online vendor automatically pulls payment from a customer’s account with prior authorization).

NACHA explains that ACH payments can be either credit or debit, and are especially suited for large volumes of recurring transfers with known counterparties – such as salaries, pensions, tax refunds, subscription fees, and business-to-business invoices.

How an ACH Transfer Works

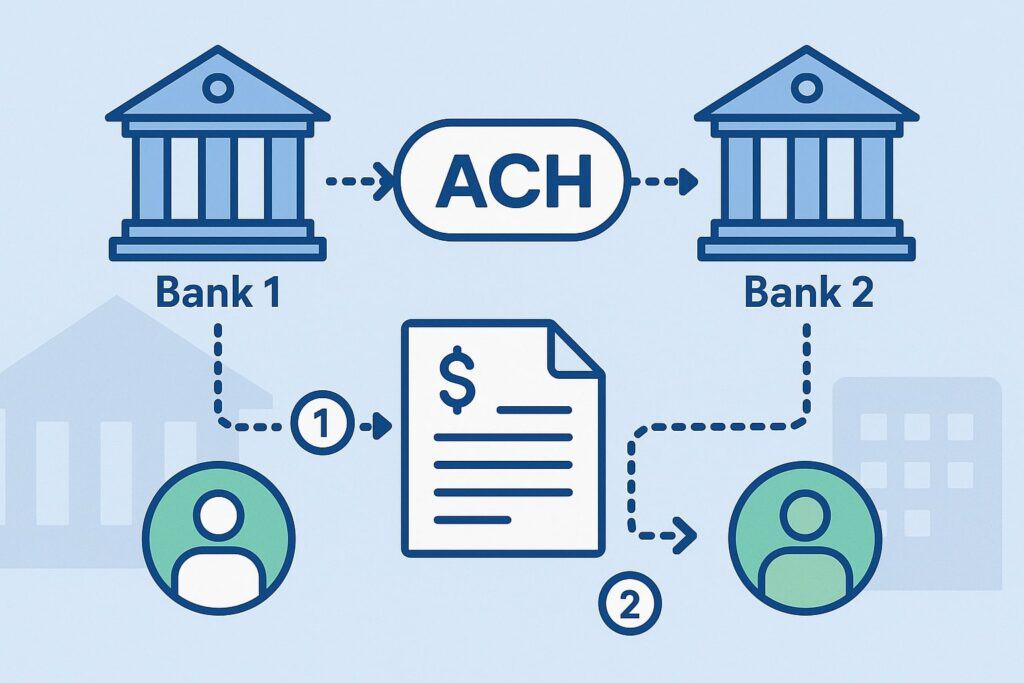

At a high level, an ACH transfer involves several steps and parties. Consider a simple scenario: you (the originator) want to send $500 from your bank account to a supplier’s bank account. Here’s what happens:

- Initiation by Originator. You authorize a payment – for instance by scheduling an online payment or giving your supplier your account information. This can be a one-time instruction or a recurring authorization. The party initiating payment is called the originator.

- Originating Bank (ODFI). Your bank (the Originating Depository Financial Institution, or ODFI) collects this instruction along with any others received. Your payment instruction (an ACH entry) is then grouped into a batch of transactions. Large banks and payment processors accumulate ACH instructions throughout the day.

- ACH Operator. At set times, the ODFI sends the batch of ACH entries to an ACH operator. There are two such operators in the U.S.: the Federal Reserve’s ACH service and the Electronic Payments Network (operated by The Clearing House).

The operator plays a central clearing role. It receives all the batches from many originating banks and then sorts the transactions by destination bank. - Receiving Bank (RDFI). After sorting, the ACH operator forwards each transaction to the appropriate bank – the Receiving Depository Financial Institution (RDFI). The RDFI is the payee’s bank.

Upon receiving the entry, the RDFI credits (or debits) the beneficiary’s account. In our example, the supplier’s bank credits $500 to the supplier’s account, while your bank debits $500 from your account (the two accounts balance out).

Investopedia describes this flow succinctly: “An ACH transaction begins when an originator initiates a direct deposit or direct payment on the ACH network. The originator’s bank (ODFI) collects multiple incoming ACH requests and groups them into batches.

An ACH operator (either the Federal Reserve or a clearinghouse) receives the batch of ACH transactions. The ACH operator sorts the batch and makes transactions available to the bank or financial institution of the intended recipient (the RDFI).

Finally, the recipient’s bank account is debited or credited, thus ending the transaction.”. In other words, the network is essentially a batch-processing clearinghouse: your payment is bundled with others and later delivered to the recipient’s bank in bulk.

Because ACH transactions are sent in batches at scheduled intervals, they do not happen in real time. By default, when a bank submits an ACH entry it is not final until it is cleared and settled in one of the processing windows.

NACHA sets the settlement windows and deadlines. Generally, if an entry misses the same-day window, an ACH credit will settle by the following business day and an ACH debit by the next morning.

However, since 2016 (and fully by 2018) NACHA has offered Same-Day ACH for faster movement: if a batch is submitted early enough (in one of multiple windows each day) and marked for same-day service, the transaction can clear on the same banking day.

Key points about ACH processing include:

- Batch Settlement. ACH operators typically run several processing cycles per banking day. NACHA rules require multiple settlement windows (currently three same-day windows, plus next-day processing for unsettled entries).

As of 2023, the Federal Reserve reports it processes ACH entries six times per day, and NACHA notes ACH settles four times daily. - Account and Routing Numbers. Every ACH transfer requires the bank routing number and the recipient’s account number. In fact, an ACH cannot be processed without those details.

(For this reason, utilities or businesses asking for your bank info will ask for these numbers.) NACHA rules make clear that an ACH entry includes the ABA routing transit number of the receiving bank and the beneficiary’s account number.

(Sometimes people also supply a “financial institution name” or beneficiary name.) Tipalti’s payments guide sums it up: to send any domestic ACH, “you must have the account number and routing number for both the sending and receiving parties. An ACH will not process without this information”. - Direct Deposit Example. One of the most common ACH uses is direct deposit of paychecks or benefits. For instance, employers submit payroll runs via ACH credits. On payday, each employee’s ODFI batches all salaries and sends them out.

The ACH operators deliver these to the various banks (RDFIs), and the employees see the funds in their account. NACHA emphasizes that direct deposit is reliable: if payday falls on a weekday, the funds will be in accounts by 9 a.m. that morning.

In fact, NACHA reports that an ACH payroll deposited on Friday is available by Friday morning in all cases (i.e. the weekend doesn’t delay disbursement).

Types of ACH Transactions

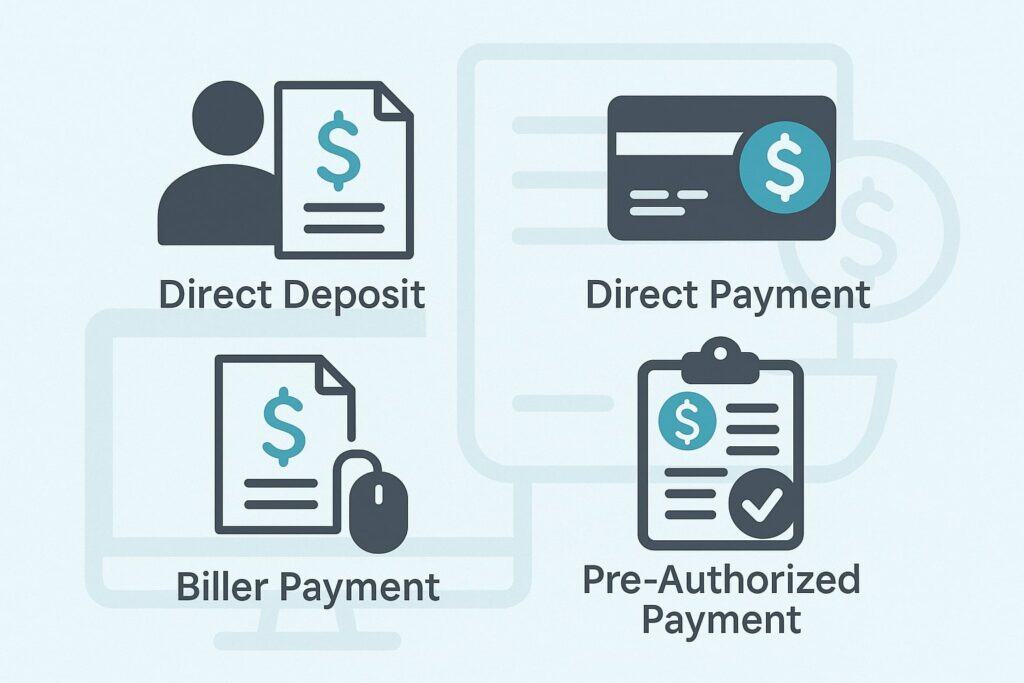

ACH transactions come in a few varieties. The two core categories are:

- ACH Credit (Push). The payer initiates the payment by instructing their bank to push funds to the recipient.

Common examples: direct deposit of payroll or retirement checks (the company pushes salaries), business-to-business payments where a vendor or client pays bills by initiating an ACH credit, or one-time payments where a payer sets up the transaction.

Under NACHA terminology, the originator sends a credit entry. From the payee’s perspective, they receive an ACH credit into their account. - ACH Debit (Pull). The payee or merchant initiates the transfer by pulling funds from the payer’s account (with prior authorization).

For instance, when you set up automatic bill pay for your utilities, the utility company arranges an ACH debit to pull the monthly bill from your bank. Or, a company might process a credit card-like payment by pulling money via ACH.

From the payer’s bank perspective, an ACH debit is the originator’s instruction to debit (remove) funds from the account. From the payee’s view, they get an ACH credit once the entry clears.

NACHA highlights that scheduled recurring payments are particularly well-suited to ACH. Payroll direct deposits, pension disbursements, insurance premium payments, subscription services, mortgage and utility bills, tax payments – all these often run as recurring ACH entries on set dates.

In fact, many fintech and payment apps use ACH behind the scenes. Tipalti’s guide notes that popular person-to-person payment apps (Venmo, PayPal, Cash App, Zelle) all use the ACH direct-payment method under the hood when moving funds to users’ bank accounts. (We’ll compare some of these later.)

ACH transactions also have specialized subtypes:

- Same-Day ACH. NACHA’s enhanced service. By opting to process within a same-day window, many ACH payments (up to $1,000,000 per transaction as of 2022) can settle on the same business day, often within a few hours. This is now widely used for urgent transfers (e.g. last-minute payroll, emergency payments).

- International ACH (IAT). Though the core U.S. ACH network is domestic, there is a category called IAT for certain cross-border ACH entries.

If a U.S. bank needs to send money overseas through ACH, it must use the IAT format (which includes extra information for currency conversion and compliance).

However, conventional ACH is generally limited to U.S. and U.S. territories. For truly global transfers, other systems (SWIFT wires, alternative rails) are typically used.

Push vs. Pull and Authorization

An important distinction is who initiates the transfer. With an ACH credit (push), the payer (originator) instructs their bank to send money. With an ACH debit (pull), the payee (receiver) has pre-authorization to draw funds from the payer’s account.

This “pull” feature is a key use case: for example, businesses often use ACH debits to collect monthly subscriptions or bills automatically. Plaid explains: “ACH transfers are bi-directional… The receiver can initiate a transaction on behalf of the sender.

This makes them suitable for recurring use cases.”. In practice, ACH debits require that the payee have the payer’s bank information and permission (often via signed authorization).

The pulling nature of debits means payers must monitor their accounts for ACH entries; NACHA rules allow consumers to dispute unauthorized debits (often up to 60 days after they appear).

In summary, whether it’s push or pull, ACH entries travel the same network and have similar settlement times. Both credits and debits typically clear within a day or two under standard rules.

NACHA’s operating rules provide separate processing deadlines, but fundamentally an ACH is just a data message that leads to a transfer of funds once both sides reconcile.

Timing and Settlement

A frequent question is how long an ACH transfer takes. Timing depends on when the entry is submitted and the rules in effect. In general:

- Standard ACH (next-day). Most ACH transfers settle in 1–3 business days. For example, Investopedia notes that “NACHA rules state that the average ACH debit settles within one business day, and the average ACH credit settles within one to two business days.”

Concretely, if you initiate a routine ACH payment on Monday, a debit might post to the recipient’s account by Tuesday morning, while a credit might post by Wednesday, depending on cut-off times.

Bank holidays and weekends typically extend the timeline, since the Federal Reserve does not settle ACH on weekends or federal holidays. - Same-Day ACH. To speed things up, most banks now offer Same-Day ACH at little or no extra cost for many transactions. NACHA phased this in the beginning in 2016.

Today, if an originator sends an ACH file early enough in the day (typically before the final same-day window, e.g. 4:45 p.m. ET) and marks it for same-day processing, the funds can settle that same business day (often in a few hours).

NACHA’s fact sheet highlights that Same-Day ACH (up to $1 million per payment) allows many payments to be sent and received on the same banking day. This is especially useful for emergency payroll, expedited bill payments, or business transactions that can’t wait a few days. - Settlement Windows. The ACH network does not continuously settle transactions; it batches them into “windows.” Traditionally, there were two daily processing windows. By 1993 this had expanded to four batch times per day.

As of 2023, the Federal Reserve says it processes ACH entries six times a day, and NACHA reports funds settle four times daily.

For same-day ACH, NACHA added more windows (now three settlement cut-offs). If an entry misses the same-day windows, it simply waits until the next cycle (one or two days later). - Real-Time Alternatives. In contrast, some newer systems enable instant settlement. Notably, the Federal Reserve’s FedNow service (launched July 2023) provides real-time gross settlement of payments at any time or day.

Similarly, The Clearing House’s RTP network (available since 2017) enables immediate transfers between participating banks. These modern rails settle instantly (round-the-clock), whereas ACH remains a batch system tied to banking hours.

NACHA acknowledges these newer options as complementary: its fact sheet notes that instant rails (FedNow and RTP) “provide payment system users a choice based on their use case” alongside ACH.

In other words, ACH wasn’t designed for instant consumer-to-consumer transfers, so FedNow and RTP fill that niche. However, ACH continues to handle the vast bulk of standard salary and bill payments.

Advantages of ACH Transfers

ACH transfers have many benefits, which explain why the network is so widely used:

- Broad Reach and Interoperability. The ACH network reaches virtually every U.S. bank and credit union. Whether you’re a large corporation or a small business, you can send or receive ACH transactions through your financial institution.

All participating banks interconnect through the ACH operators, so any bank’s ACH entry can reach any other bank in the network. - Low Cost. ACH is extremely cost-effective. Banks and processors handle large batches of transfers, minimizing per-transaction costs. Plaid explains that consumers “do not usually pay a fee” for ACH payments.

Instead, any fees are typically charged to the business or originator (and even those are quite small). For example, some banks might charge $0.25–$1.00 per ACH; others include it in service or package deals.

Compare this to wire transfers, which commonly charge $25–$35 per domestic transfer. Even international ACH (IAT) usually costs less than a comparable wire. In short, ACH allows companies to automate large payment volumes at a tiny fraction of the cost of manual or real-time methods. - Efficiency and Automation. Because ACH is electronic, it eliminates paper and manual processes. Businesses can set up recurring payments easily (e.g. for payroll or subscriptions) without human intervention each time.

NACHA notes that the ACH network has “improved the efficiency and timeliness of government and business transactions”. Likewise, consumers enjoy automatic bill pay features in online banking – all enabled by ACH. - Timeliness for Recurring Payments. ACH transfers are reliable enough that critical payments depend on them. As noted, NACHA guarantees payroll direct deposits by 9 a.m. on payday.

Many businesses pay rent, mortgage, payroll, and vendor invoices via ACH on strict schedules, knowing funds will arrive as expected. The advent of Same-Day ACH has added flexibility: companies can pay emergency bills or bonus payroll runs on short notice and still rely on ACH’s schedule. - Security (Compared to Checks). ACH is considered safer than paper methods. NACHA explicitly points out that paper checks are the method “most prone to fraud”, and it advocates migration to electronic ACH payments.

ACH transactions are encrypted and processed through regulated financial networks. Fraud can occur (for example, if someone obtains bank account details), but the risk is generally lower than with checks (which can be stolen, forged, or altered).

Additionally, ACH entry formats and NACHA rules help prevent unauthorized transactions. For example, a merchant pulling an ACH debit must present valid authorization or risk being reversed.

NACHA even provides consumer guidance on watching for ACH scams. Overall, electronic payments like ACH are viewed as a safer, more auditable alternative to cash or checks. - Scalability. The ACH network can handle enormous volume. According to NACHA statistics, 33.6 billion ACH payments flowed in 2024, up from about 18 billion in 2022.

In fact, over the last decade ACH volumes have grown strongly (approximately 5.7% per year, and total value doubled from 2015 to 2024). This demonstrates that the network is robust and can scale to meet increasing electronic payment demands.

Businesses know they can rely on ACH even for large aggregate payrolls or many thousands of bill payments every month.

In short, ACH transfers are cheap, reliable, and ubiquitous. For most routine domestic payments (payroll, bills, vendor payments, tuition, taxes, etc.), ACH is often the default method in the U.S.

Limitations and Risks of ACH

While ACH has many strengths, it also has some limitations that users should be aware of:

- Speed (Delays). The biggest drawback of ACH is timing. A standard ACH transfer takes longer than a wire or an instant payment. We noted above that typical ACH clears in 1–3 business days. This means you cannot rely on it for immediate funding needs.

If you need same-day funds, you must explicitly use Same-Day ACH (if available) or a wire/instant transfer. Many fraud or bill-payment frauds exploit the lag time of ACH (e.g. B2B fraud where a bad actor hijacks a payment and the victim doesn’t realize for days).

That said, same-day options and extended windows mitigate this somewhat, but ACH is fundamentally not “real-time”. - Limits and Holds. Banks may impose maximum limits on ACH transfers for security or regulatory reasons. For consumers, daily or weekly ACH transfer limits (set by the bank) are common.

For example, some banks might cap an online transfer to $5,000 or $10,000 per transaction (or similar per-day limits). While the network itself allows up to $1 million on Same-Day ACH (as of 2022), individual banks often set lower caps.

Moreover, if you initiate a large ACH debit to your account (e.g. a big bill), your bank might delay posting it until it confirms sufficient funds. Tipalti’s guide warns that an ACH will not go through without needed account numbers, but it also notes banks will place holds or reject transfers if rules (like insufficient funds) apply. - Revocability. Unlike wires (which become final once sent), some ACH transfers can be reversed or returned after they hit an account. Under NACHA rules, a recipient can dispute unauthorized debits for up to 60 days after the statement date.

Also, technical errors (wrong account number) or duplicate entries allow reversals (return to sender) within a few days. This is good for correcting mistakes, but it means receiving an ACH credit isn’t immediately “perfectly final” until several days have passed.

On the other hand, from the payer’s perspective, an initiated ACH cannot be easily cancelled once sent (it must generally run its course to settlement).

Plaid explains: “ACH transfers can’t be canceled but can be recalled or disputed”. Thus, both senders and receivers must manage ACH timing carefully. - Domestic Only (Mostly). The standard U.S. ACH network covers the United States and U.S. territories. It is not designed for international remittances.

While NACHA’s International ACH Transactions (IAT) allow certain cross-border payments, these are used only in specific cases (e.g. U.S. companies paying foreign vendors under contracts).

For sending money abroad or across currencies, one must use wire transfers (SWIFT), specialized “global ACH” services, or online remittance platforms. In other words, if you want to send money to a foreign bank account not linked to the U.S. ACH, you cannot use standard ACH. - Fraud Risk. Though relatively secure, ACH is still vulnerable to certain scams. Common schemes include Business Email Compromise (where a company’s invoice is switched to a fraudster’s account), and malicious ACH debits on compromised accounts.

NACHA and banks warn consumers and businesses to verify instructions and guard account details. If an unauthorized ACH debit occurs, law provides some consumer protection (via Regulation E for consumer accounts), but businesses have less leeway.

In practice, most ACH scams are caught within days, but they underscore the need for vigilance. Compared to checks, ACH fraud is less common, but it’s not zero.

For example, fraudster Phishers might trick someone into authorizing an ACH debit to an account they control. Users should always verify ACH requests and review account statements. - No Immediate PayPal-Style “Escrow.” Some payment services (like PayPal or credit cards) offer buyer protection or hold on payments in case of disputes. Traditional ACH lacks such consumer protections built into the network.

Once an ACH credit is deposited, the money is available (subject to return rules). For standard consumer purchases, people sometimes prefer credit cards or payment apps because they can initiate chargebacks if things go wrong. ACH doesn’t offer the same level of recourse for general purchases.

In sum, ACH works very well for routine planned payments but is not a quick-transfer solution for urgent or unfamiliar transactions. Users should plan ahead for timing and be aware of any bank-imposed limits or fees.

ACH Transfer Fees and Costs

One of the biggest advantages of ACH is its low cost, but there can still be fees involved:

- Consumer Fees. Most banks do not charge individual consumers a fee for making or receiving ACH transfers. For example, if you log into your bank’s website and transfer money to another account at another bank (an ACH), typically it’s free.

Many online bill-pay services (bank’s bill pay) use ACH and do not add per-transaction fees for customers. In some cases, a bank might charge a small fee for express or expedited transfer (though often they limit it to wire services, not ACH). Overall, consumers rarely pay anything extra for an ordinary ACH. - Originator/Business Fees. Businesses, fintech firms, and nonprofits that send ACH payments often pay nominal fees to their bank or processor. These might be on the order of $0.10–$0.30 per transaction for large volumes, or up to $1.00 per transaction for smaller batches.

The key point is that even these fees are very small compared to the payment amounts. For instance, if a business is processing payroll by ACH, it might pay a flat fee like $0.25 per employee pay run.

Plaid notes that transaction fees for ACH are “rarely passed on to consumers,” and banks’ internal costs are often fractions of a cent per transfer. If you’re a customer receiving an ACH credit (like payroll or a refund), you almost never see a fee deducted. - International Fees. If using the U.S. ACH to send money overseas (via IAT), there may be currency conversion fees or international transaction fees, similar to wire fees but usually lower. We won’t detail these here since cross-border ACH is specialized and often done via a partner network.

- Express Options. Some banks offer “ACH before noon” or same-day features with nominal fees. For example, a business might pay a bank an extra $10–$20 per same-day ACH batch.

Additionally, fintech apps may charge a percentage (like Venmo’s 1.75% instant transfer fee). But standard ACH credit/debit itself remains low-cost.

By comparison, it’s illustrative that wire transfers typically cost tens of dollars. According to Plaid, domestic wires can cost up to ~$35 for senders and $20 for receivers. ACH fees are a tiny fraction of that. So for most routine payments, ACH is by far the cheapest option.

Security and Regulation

The ACH network is heavily regulated. NACHA’s operating rules ensure participants follow strong security and compliance standards. Key security features include:

- Data Encryption and Secure Networks. Banks and ACH operators use encrypted communication for ACH files. Sensitive banking details are protected in transit between institutions.

- Authorized Transactions Only. NACHA rules require that ACH debits (pulls) be authorized in writing or electronically by the account holder before processing. Originators must retain proof of authorization for several years. Unauthorized debits can be disputed.

- OSHA and OFAC Compliance. Banks must screen ACH transactions under U.S. federal regulations (e.g. Office of Foreign Assets Control) to prevent payments to blocked entities.

- Failure Handling. If an ACH entry is invalid (wrong account number) or if the account has insufficient funds, the entry is “returned” (rejected) under standard return codes.

For example, a debit will bounce and the originator is notified (and possibly fined a return fee). This provides a built-in quality check, unlike a paper check that might just bounce later.

Customers should also protect their own information (account/routing numbers) and beware of phishing attempts. NACHA’s website includes consumer alerts about common ACH scams (e.g. people impersonating creditors or instructing unauthorized debits).

In practice, while ACH is very secure in terms of banking infrastructure, many frauds occur at the user level (like giving account info to a scammer). Overall, using the ACH network is considered quite secure, especially compared to paper-based payments.

Comparing ACH Transfers to Other Payment Methods

To understand ACH fully, it’s helpful to compare it with other ways of moving money:

ACH vs. Wire Transfer

- Speed. Wire transfers (domestic) are much faster than standard ACH. A Fedwire or bank wire initiated on a weekday typically clears and settles within the same day (often within minutes or hours). In contrast, a regular ACH transfer (non-same-day) usually takes 1–3 business days to finalize.

Plaid summarizes: “Domestic wire transfers usually clear within minutes… ACH transfers can take between hours and days to both clear and settle.”. (Note: with Same-Day ACH, some ACH payments can also clear on the same day if sent early enough, narrowing this gap slightly.) - Cost. Wires cost significantly more. A domestic wire fee is often in the $25–$35 range per transfer for the sender (and sometimes $10–$20 for the receiver). ACH, by contrast, is almost free for consumers (and only a few cents for businesses).

For example, Wise notes ACH fees are usually “around $0 to $5” (depending on the bank) and wires may be up to $50. In practice, when deciding between a wire and an ACH, organizations often consider whether speed justifies the cost. - Reversibility. Wire transfers are effectively final once completed. You cannot recall a wire after it settles (barring extraordinary measures). ACH transfers, however, can sometimes be reversed or returned under NACHA’s rules.

For instance, if an ACH debit is unauthorized, the bank can reverse it within 60 days of the statement date. Similarly, clerical errors (wrong account number) allow returns.

However, this means recipients sometimes see funds credited and then later debited back. This flexibility is a double-edged sword – it offers error protection but can be a headache if misused. Wires don’t have that built-in recall window. - Use Cases. Wires are typically used for large, one-time or time-critical payments. For example, wires move real estate closings, cross-border corporate payments, or large institutional transfers where time is of the essence.

ACH is preferred for routine, possibly smaller or recurring transactions. As Plaid notes, ACH is well-suited to high-volume, recurring transactions (like payroll, subscriptions, vendor payments), whereas wires are usually one-off.

Additionally, ACH supports both pull and push, whereas wires only push money (only the sender can initiate a wire). Finally, ACH payments can be scheduled and automated easily in accounting systems; wires usually require manual entry and are settled individually.

ACH vs. Peer-to-Peer (Zelle, Venmo, Cash App)

- Zelle and Bank P2P. Zelle is a U.S. bank-backed P2P transfer service. Many people wonder: Is Zelle just an ACH? The answer is that Zelle leverages the same bank account rails but is engineered for speed.

Wise explicitly calls Zelle “an ACH – an electronic transfer between US banks”, but notes that Zelle makes funds available to the recipient within minutes. Zelle itself is free (through most bank apps) and sends money almost instantly to another Zelle user.

In practical terms, when you hit send in Zelle, the sending and receiving banks coordinate so quickly it feels instant – but behind the scenes they may be using a combination of ACH and realtime settlement. In contrast, a traditional ACH transfer takes days.

For example, Wise’s comparison chart shows Zelle sends (free) in minutes, whereas a standard ACH can take up to 3 days. Another key difference: Zelle is only for P2P domestic transfers (no international use, and limits on amount – e.g. ~$500 per week for many banks).

ACH has higher limits (up to $1M for Same-Day ACH) and can be used by businesses and for bill payments, not just person-to-person. - Venmo, Cash App, PayPal. These popular apps also ultimately move money via ACH when transferring funds to/from bank accounts.

For instance, Venmo offers two options: a standard bank transfer (free, but completed in 1–3 business days via ACH) or an instant transfer (which uses debit card networks to send money to your bank in ~30 minutes, for a ~1.75% fee).

In other words, if you tell Venmo to deposit money to your bank without selecting “instant”, Venmo will ACH the funds and it will take a few days.

Cash App and PayPal work similarly: standard withdrawals are ACH and take 1–3 days, while instant (for a small fee) use other rails.

The key takeaway is that behind the scenes, the default “free” transfers of these apps rely on the ACH network. Their competitive advantage (instant option, social interface) sits on top of ACH’s capabilities. - Other P2P Services. Some fintechs (like Wise and TransferWise) may use local ACH or RTP rails to facilitate international or domestic money movements, but they are essentially intermediaries. Most entirely outside-the-banks P2P methods (like cryptocurrencies) are not ACH at all.

Overall, the landscape is: Zelle/Venmo/CashApp = faster, user-friendly P2P using bank rails; ACH = the behind-the-scenes engine for most bank transfers between accounts (slower, cheaper, general-purpose).

ACH vs. Credit/Debit Card Transfers

Though different in nature, it’s worth noting that paying with a debit or credit card is also an electronic transfer, but not via ACH. Card payments go through Visa/Mastercard networks.

A debit-card “bank transfer” (e.g. sending money using a debit card number) would typically be treated like an instant card payment, separate from ACH. Credit card transfers (like credit card ACH) are entirely different due to how merchants are billed.

The main point: ACH is direct bank-to-bank, whereas card payments involve merchants acquiring banks and card networks. Cards are immediate but carry processing fees (~1–3%) that are much higher than ACH’s cost.

For consumers, cards offer rewards and fraud protection, but ACH is more cost-effective and used for direct account payments (especially recurring) that don’t need the protections of a credit card.

ACH vs. Paper Checks

ACH was explicitly designed to replace many check payments. Compared to checks, ACH is far faster and more reliable. A check payment requires printing, mailing, manual deposit, and multi-day bank processing – often taking a week or more to fully clear.

By contrast, ACH is entirely electronic. NACHA’s fact sheet points out that checks are inefficient and prone to fraud, and encourages migration to electronic methods. Most utility companies, landlords, and employers now prefer ACH (direct withdrawal or deposit) over paper checks. Today, businesses often ask customers to “pay by ACH instead of check” for this reason.

However, one difference is consumer familiarity: not everyone has used ACH (especially older generations), and checks offer a “paper trail” that some like. Yet the check usage continues to decline as ACH and mobile banking grow.

FedNow and Real-Time Rails

Finally, it’s worth contrasting ACH with the brand-new FedNow instant payment network. FedNow (launched 2023) enables real-time, 24/7 transfers of funds (final settlement in seconds) between participating banks.

By contrast, ACH only runs on banking days. NACHA’s guidance notes that instant payments (FedNow and The Clearing House’s RTP) are complementary to ACH. They serve different needs: FedNow/RTP for immediate transfers at any time (even holidays), ACH for bulk, scheduled transfers on business days.

Over time, more banks are expected to adopt FedNow, but ACH remains the workhorse for batch payments. Businesses may eventually choose FedNow for faster vendor payments, but for now ACH is ubiquitous and FedNow is still building adoption.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What exactly is an ACH transfer?

A: An ACH transfer (Automated Clearing House transfer) is an electronic funds transfer between U.S. bank accounts, processed through the national ACH network. It replaces many paper-check transactions.

For example, when your employer pays your salary by direct deposit, or when you pay your utilities online from your bank account, those are ACH transfers. The term ACH comes from the Fed’s automated clearing house system established in the 1970s.

It is managed by NACHA, and connects all U.S. banks. In short, an ACH transfer moves money in batches from one bank to another via a secure electronic system.

Q: How does an ACH transfer work in practice?

A: In practice, ACH transfers involve two banks and the ACH clearing network. You (the sender/originator) instruct your bank to send money to someone else’s account. Your bank (the ODFI) collects your and others’ transfer instructions into a batch file.

This batch goes to an ACH operator (like the Federal Reserve’s ACH). The operator sorts the batch and sends each transfer to the recipient’s bank (the RDFI). The recipient’s bank then credits the beneficiary’s account.

Essentially: you start the payment → your bank batches it → ACH operator processes it → recipient’s bank receives it. This usually takes 1–3 business days total (unless same-day service is used).

Q: How long does an ACH transfer take?

A: A standard ACH transfer usually takes 1 to 3 business days. For a typical consumer or business payment, expect the money to move within a couple of days. NACHA rules indicate an average ACH debit clears in 1 day and a credit in 1–2 days.

The exact timing depends on when you initiate the transfer (before or after the processing cutoff) and whether you choose same-day processing.

If you pay during a same-day window and opt for same-day ACH, the transfer can clear on the same business day (often within hours). Note weekends and bank holidays add a day or two. In contrast, a wire transfer typically completes on the same day.

Q: What’s the difference between an ACH credit and an ACH debit?

A: The difference is who initiates the transfer. With an ACH credit, the payer initiates and pushes money to the recipient. Examples: your employer pushing payroll into your account, or you using online banking to send a one-time payment to someone.

With an ACH debit, the payee (recipient) initiates by pulling funds from the payer’s account (after the payer authorized it). Common examples: automatic bill payments, subscriptions, or a mobile payment app charging your account.

In banking terms, ACH credits are often “push payments” and ACH debits are “pull payments.” Both use the ACH network, but the direction and authorization differ. NACHA notes that ACH is well-suited for both types, which makes it flexible for many use cases.

Q: Do I need a special account to send or receive an ACH transfer?

A: No special account is needed. Any standard U.S. checking or savings account can send and receive ACH transfers, as long as your bank or credit union participates in ACH (virtually all do). You will need to provide your ABA routing number and account number to the sender (for credits) or to the payee (for debits).

As mentioned earlier, an ACH cannot process without these numbers. Some banks may also require account name or type, but the critical pieces are the routing and account numbers.

Q: Are ACH transfers safe? Can they be reversed?

A: ACH transfers are generally very safe and encrypted in transit. Because the network is regulated by NACHA and backed by federal system safeguards, the infrastructure is robust. However, like any payment system, there is some risk of fraud (e.g. unauthorized debits).

For consumers, U.S. law (Regulation E) gives you the right to dispute unauthorized ACH debits and get your money back in most cases. That can happen if a wrong number was keyed or if fraud occurred; banks handle such returns according to NACHA rules.

One difference from wire transfers is that ACH entries can be returned or reversed: for example, a recipient can dispute a debit within 60 days, or an entry can be returned for technical reasons (insufficient funds, incorrect info).

Wires, once settled, are usually irreversible. So while ACH is secure, recipients sometimes see payments returned.

Q: How much do ACH transfers cost?

A: For most consumers, nothing. Sending or receiving ACH through your personal bank account is typically free. No bank I know charges consumers a fee for standard ACH transfers (some might charge for expedited or for very large accounts, but it’s uncommon).

Businesses or payments companies initiating ACH may pay a small fee per transaction (often cents per transfer) to their bank. For perspective, a business might pay $0.10–$0.50 to send an ACH, whereas a wire costs $20+.

So in everyday use, ACH is very low-cost. If you’re using an app like Venmo or PayPal, the free standard transfer to your bank is actually an ACH (taking 1-3 days), whereas their instant transfers (for a small percentage fee) use card rails.

Q: Can I send money internationally with ACH?

A: The U.S. ACH network itself covers domestic (and U.S. territory) accounts only. You cannot use standard ACH to send money to someone’s bank in another country.

(There is an international ACH option, but it’s a specialized format called IAT and works mainly for specific business or payroll uses, not general consumer remittances.) For international transfers, people typically use wire transfers (SWIFT), or online services like Wise, Western Union, or cryptocurrency solutions.

Q: What is NACHA and the Federal Reserve’s role?

A: NACHA is the National Automated Clearing House Association. It’s a nonprofit organization that sets the rules and standards for ACH transactions. NACHA does not actually move the money; it governs the network.

The actual clearing is done by two ACH operators: the Federal Reserve (FedACH) and The Clearing House (Electronic Payments Network). The Fed, via its ACH service, acts as a 24/7 operator (on business days) for many banks.

So when you send an ACH, it’s likely the Fed that will relay it to the recipient bank. The Fed also participates in industry efforts to improve ACH (such as adding same-day windows). In summary, NACHA writes the playbook, and the Fed & EPN actually process the plays.

Q: Is ACH used outside the United States?

A: “ACH” is a U.S. term. Other countries have similar systems (for example, the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) in Europe).

However, if you’re in the U.S. sending to a U.S. account, it’s ACH. If you have foreign bank accounts, you would use that country’s local system or international wires. The U.S. ACH network does not cover foreign accounts.

Conclusion

An ACH transfer is a cornerstone of the U.S. payment system. It’s a batch-based electronic transfer service that banks and businesses use to move money reliably and cheaply. While not instantaneous like a wire or a new real-time rail, ACH offers unbeatable efficiency for routine payments.

You’ll find ACH behind almost every direct deposit, bill pay, vendor payment and app-to-bank transfer in the country. Its advantages – low cost, ubiquity, and automated handling of recurring payments – make it extremely valuable for employers, payees, and the economy at large.

When considering payment options, remember: ACH is ideal for non-urgent transfers between U.S. accounts, especially if you want to avoid fees.

For example, use ACH for payroll, subscription services, or paying friends via bank (and count on a day or two for processing). Use faster rails (wires, FedNow, or P2P apps) when you truly need instant delivery and are willing to pay for it. Keeping these differences in mind helps businesses and individuals choose the best method for each situation.

As payment technology evolves (with Same-Day ACH, FedNow, digital wallets, etc.), the ACH network remains central. Even as instant payments become more common, ACH will likely continue to handle the high-volume, trusted bulk of U.S. financial transfers.

It’s a mature, reliable system – the digital successor to paper checks – that quietly moves trillions of dollars every year. Understanding ACH transfers means understanding how modern banking really works behind the scenes.